Open water is a critical ingredient in winter birding; without it, your birding repertoire will be limited to a few dozen passerines. The recent deep freeze has concentrated waterfowl in the ice-jammed Ohio River. I took a cruise along the river this afternoon and found decent numbers of ducks (a flock of over a hundred Canvasbacks was a clear highlight) to reward my numbed toes.

The only birds close enough to photograph was a small pod of scaup near downtown Cincinnati. Greater Scaup were more numerous today, but I did see two Lessers. One of them is in the photo below. Can you find it?

The two scaups are so similar that I'm sure many novice birders have smashed their binoculars in frustration. At close range, the fine differences are easier to notice. In the top photo, the Lesser is leading the pack; below, it is the topmost bird.

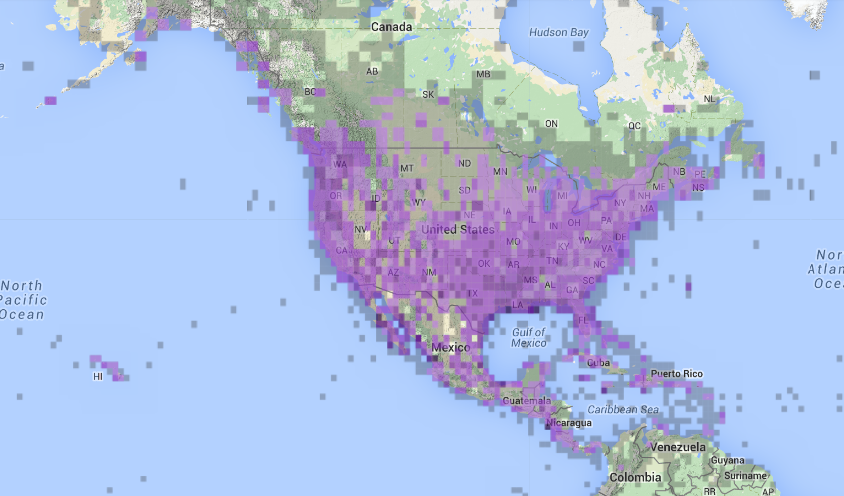

I became curious about scaup distribution--thank goodness for eBird! As I drove along, all I could remember was that Greater Scaup occurs in both the Nearctic and the Palearctic, while the Lesser lives only in North America. These maps are for winter (December through February).

Greater Scaup range--generally, it seems to stick a bit further north and seems more strongly associated with coasts.

And the Lesser Scaup. It ranges farther south and is spread more evenly across the continent.

After completing my river circuit, I made a detour on the way home to check the lake at East Fork State Park. This is a massive lake; I had a hunch there might be some open water. There was--just one small patch that was peppered with Mallards, mergansers (all three species), and goldeneye. They appeared unnerved by the pair of Bald Eagles standing vigil nearby.

Bald Eagles are certainly majestic, but after hearing several dozen breathless accounts from nonbirders about that time back in '87 when we saw an EAGLE at the cabin, they can become annoying. I'm sure these eagles are enjoying the deep freeze as much as I am--it makes hunting duck easier, a welcomed supplement to a diet of roadkill and dead fish. With temperatures predicted to rise next week, the eagles will have to go back to their carrion and I to my chickadees and White-throated Sparrows.